Five years ago, I started what seemed like a simple project: build a standalone APRS tracker that was cheap enough to lose on a high-altitude balloon flight. What followed was a journey through RF design, SMD component soldering, building a reflow oven, firmware architecture, and learning why EMI matters the hard way.

The Goal#

I wanted something practical for experimentation—a tracker that could survive being launched into the stratosphere without breaking the bank. The requirements were straightforward:

- Standalone operation (no phone, no laptop)

- Low cost (balloons don’t always come back)

- VHF radio capability for APRS

- Reliable packet transmission

I settled on the DRA818V module paired with an ESP32. The DRA818 is a simple, inexpensive VHF transceiver module that handles the RF heavy lifting, while the ESP32 provides the processing power for AFSK modulation and packet assembly.

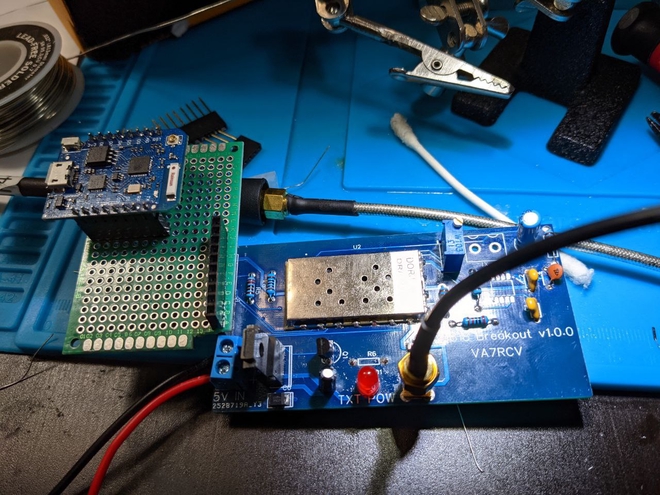

Iteration 1: The Learning Experience#

My second PCB ever. It transmitted APRS packets—technically successful—but the noise floor was terrible. I had committed every beginner PCB mistake:

- No ground planes

- Poor component placement

- Zero thought given to EMI

- Traces running wherever they felt like it

The packets worked, but the signal quality was embarrassing. This is when I discovered Electromagnetic Compatibility Engineering. That book changed everything. Suddenly, concepts like return current paths, ground plane stitching, and proper decoupling made sense.

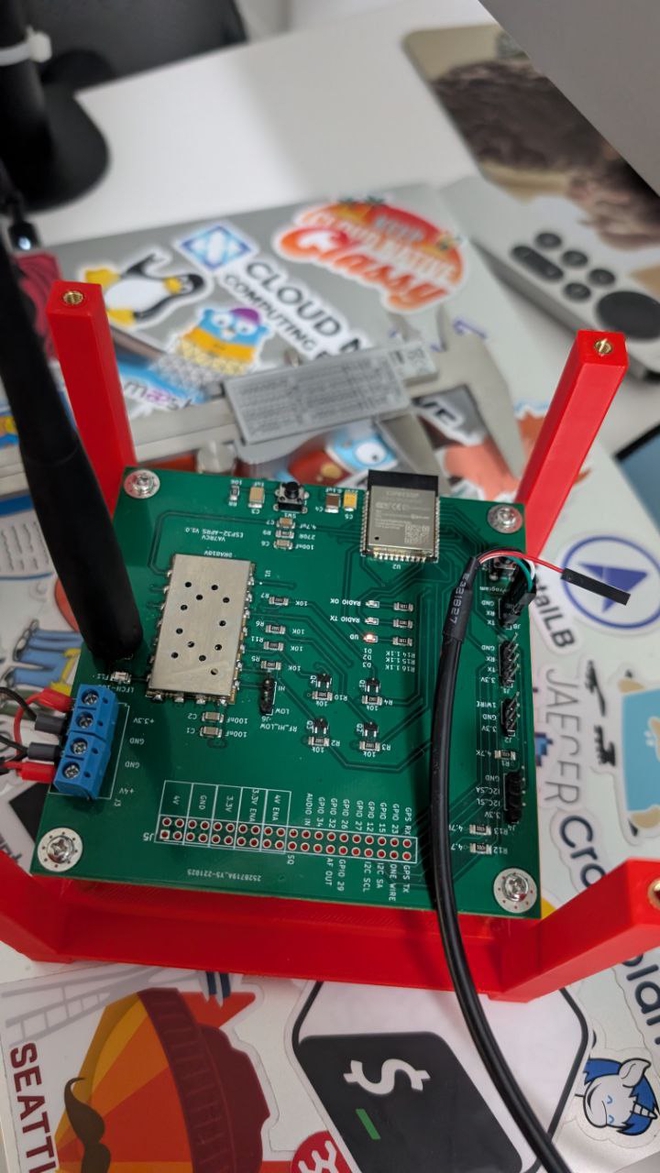

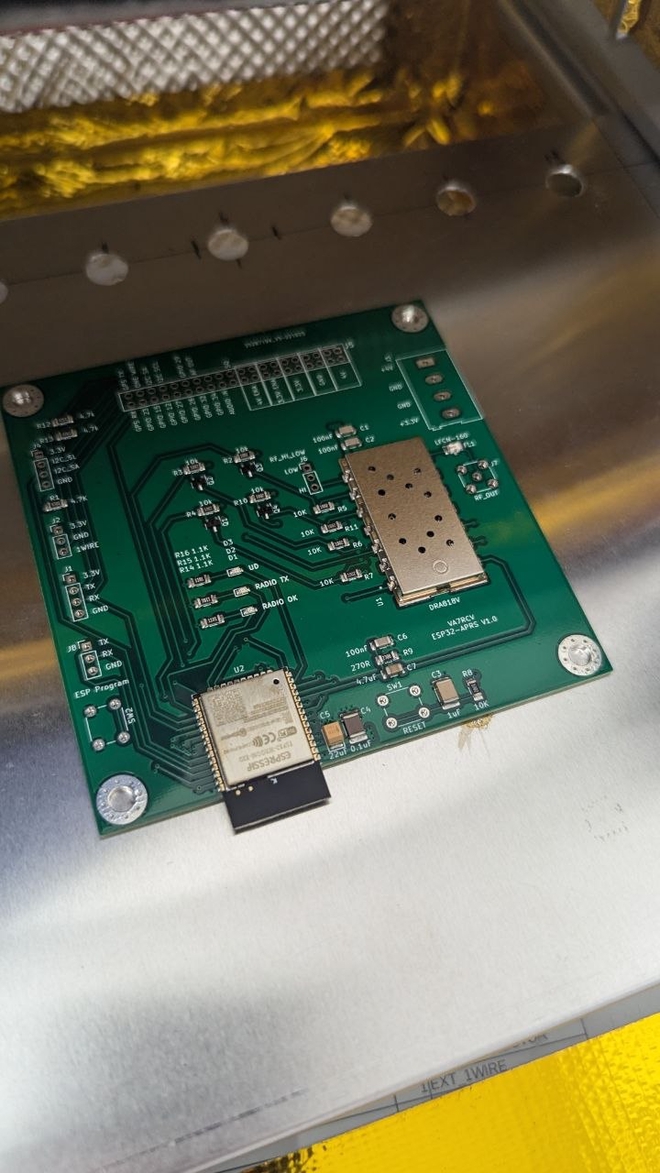

Iteration 2: Four-Layer Success#

With newfound knowledge and a switch to KiCad, I designed a proper 4-layer board:

- Dedicated ground plane

- Power plane for clean distribution

- Proper RF filtering

- Decoupling capacitors placed correctly

This design worked. Really worked. Clean signals, reliable packet transmission, and it’s been running continuously for four years without firmware updates. That’s the power of getting the hardware right.

The firmware was based on Evan Krall’s LibAPRS-esp32-i2s, trimmed down to transmit-only operation. For a balloon tracker, you don’t need receive capability—just send position reports and telemetry.

Iteration 3: Modern Firmware Architecture#

This year, I finally had time to revisit the code. The original LibAPRS library works, but it’s showing its age. The API is cumbersome, and adding features like telemetry requires digging through packet construction manually.

I rewrote the entire stack from scratch, keeping only the essential AFSK modulation and AX.25 framing:

What Changed#

Before:

// Manual packet construction

char lat[9], lon[10];

locationUpdate(gps.location.lat(), gps.location.lng());

APRS_setLat(lat);

APRS_setLon(lon);

APRS_setPower(1);

APRS_setHeight(10);

APRS_sendLoc(comment, strlen(comment));

After:

// Clean, type-safe API

aprs.sendPosition(gps.location.lat(), gps.location.lng(),

"ESP32-Tracker", 1, 1, 1, 0);

The new library handles coordinate conversion, packet formatting, and CRC calculation automatically. Adding telemetry went from manual string formatting to structured data:

APRS::TelemetryData telem;

telem.analog[0] = battery_voltage;

telem.analog[1] = temperature;

telem.analog[2] = pressure;

telem.analog[3] = humidity;

telem.analog[4] = altitude;

aprs.sendTelemetry(telem);

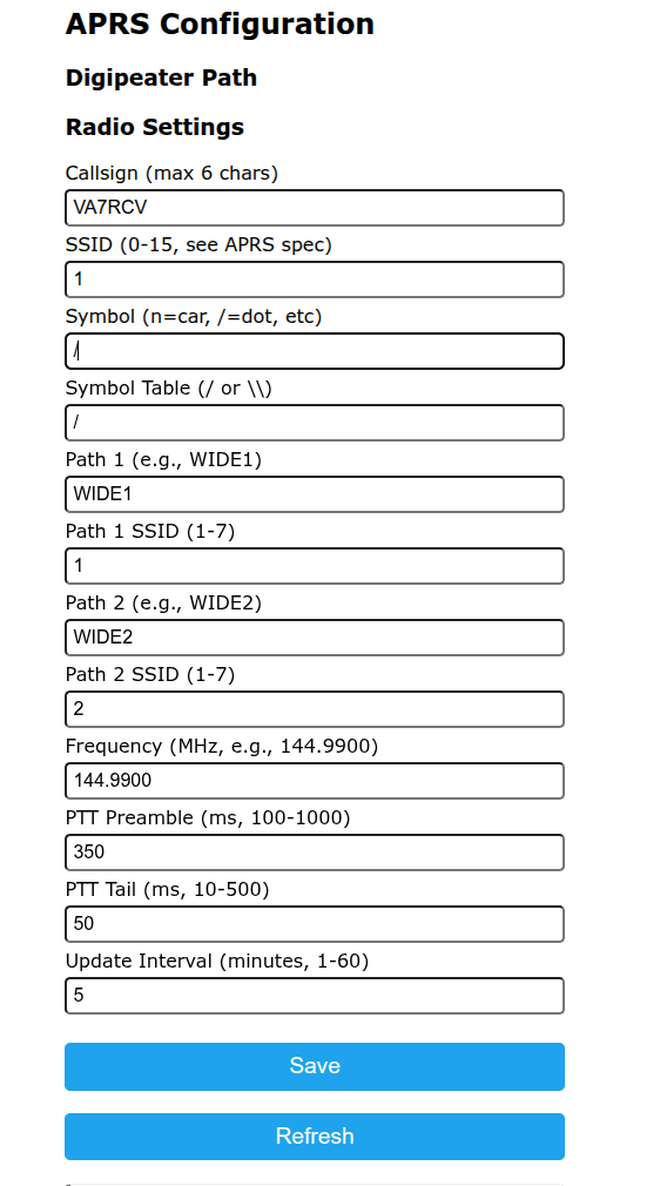

Configuration Portal#

The new firmware includes a WiFi configuration portal for field programming. Hold GPIO23 low on boot, connect to the AP, and configure:

- Callsign and SSID

- Symbol (car, balloon, etc.)

- Radio frequency

- Transmission interval

- Digipeater path

Settings persist in NVS. No more recompiling firmware to change your callsign.

How AFSK Modulation Actually Works#

APRS packets use Bell 202 AFSK (Audio Frequency Shift Keying) to encode digital data as audio tones. The concept is simple: represent binary data by switching between two frequencies. In practice, generating clean AFSK on a microcontroller requires understanding phase accumulators, sine wave synthesis, and NRZI encoding.

Direct Digital Synthesis (DDS)#

The ESP32 generates audio samples at 105,600 Hz—that’s 105,600 individual voltage levels per second sent to the DAC. To create a 1200 Hz tone, we need a sine wave that completes 1200 full cycles every second. Rather than computing sin(x) in real-time (expensive), we use a lookup table containing one quarter of a sine wave:

static const uint8_t SIN_TABLE[] = {

128, 131, 134, 137, 140, 143, 146, 149, 152, 155, 158, 162, 165, 167, 170, 173,

176, 179, 182, 185, 188, 190, 193, 196, 198, 201, 203, 206, 208, 211, 213, 215,

// ... 128 samples total (0° to 90°)

};

Each value represents a point on the sine wave from 0° to 90°. To reconstruct the full wave, we mirror this quarter-wave for 90°-180°, invert for 180°-270°, and mirror again for 270°-360°. This saves memory—128 bytes instead of 512.

The Phase Accumulator#

A phase accumulator tracks where we are in the sine wave. Think of it as an angle that wraps around from 0 to 4096 (representing 0° to 360°). Each time we generate a sample, we advance the accumulator by a phase increment:

#define SIN_LEN (512 * 8) // 4096 virtual samples

#define MARK_INC (uint16_t)(DIV_ROUND(SIN_LEN * 1200, 105600)) // ≈ 47

#define SPACE_INC (uint16_t)(DIV_ROUND(SIN_LEN * 2200, 105600)) // ≈ 85

The math: phase_increment = (table_length × frequency) / sample_rate

- MARK (1200 Hz): increment by ~47 per sample → completes one cycle every 87 samples → 1200 Hz

- SPACE (2200 Hz): increment by ~85 per sample → completes one cycle every 48 samples → 2200 Hz

Every time generateSample() is called:

_phaseAcc += _phaseInc; // Advance through the sine wave

_phaseAcc %= SIN_LEN; // Wrap at 4096

return sinSample(_phaseAcc); // Look up the sine value

The lookup function uses symmetry to reconstruct the full wave:

uint8_t Protocol::sinSample(uint16_t phase) {

uint16_t i = phase / OVERSAMPLING; // Scale down from 4096 to 512

uint16_t newI = i % (TRUE_SIN_LEN / 2); // Map to 0-255

// Mirror for second quarter (90°-180°)

newI = (newI >= (TRUE_SIN_LEN / 4)) ? (TRUE_SIN_LEN / 2 - newI - 1) : newI;

uint8_t sine = SIN_TABLE[newI]; // Look up quarter-wave value

// Invert for bottom half (180°-360°)

return (i >= (TRUE_SIN_LEN / 2)) ? (255 - sine) : sine;

}

This generates smooth sine waves with minimal CPU overhead—critical when you’re producing 105,600 samples per second.

NRZI Encoding and Bit Stuffing#

Bell 202 AFSK uses NRZI (Non-Return-to-Zero Inverted) encoding:

- A ‘1’ bit → keep the current tone (no change)

- A ‘0’ bit → switch tones (MARK ↔ SPACE)

Why? NRZI makes clock recovery easier for the receiver. The tone transitions provide timing information.

Here’s where it gets interesting. We’re transmitting the byte 0b10110011 bit-by-bit (LSB first):

Bit: 1 → stay on current tone

Bit: 1 → stay

Bit: 0 → SWITCH tone

Bit: 0 → SWITCH tone

Bit: 1 → stay

Bit: 1 → stay

Bit: 0 → SWITCH

Bit: 1 → stay

The code processes this byte-by-byte, bit-by-bit:

if (_currentOutputByte & _txBit) {

// Bit is '1' - keep current tone

_bitstuffCount++;

} else {

// Bit is '0' - switch tone

_bitstuffCount = 0;

_phaseInc = SWITCH_TONE(_phaseInc); // Toggle MARK ↔ SPACE

}

_txBit <<= 1; // Move to next bit

But there’s a problem: what if we send 0b11111111? Eight ‘1’ bits means no tone changes for 8 bit periods. The receiver loses sync. Worse, the HDLC frame delimiter is 0x7E (0b01111110)—six consecutive ‘1’ bits.

Bit stuffing solves this: after transmitting five consecutive ‘1’ bits, forcibly insert a ‘0’ (tone switch):

if (_bitStuff && _bitstuffCount >= 5) {

_bitstuffCount = 0;

_phaseInc = SWITCH_TONE(_phaseInc); // Insert a '0' by switching

}

This prevents accidental frame delimiters in the data and guarantees regular tone transitions. The receiver automatically removes these stuffed bits during decoding.

Generating the Audio Stream#

Each bit lasts SAMPLESPERBIT samples (105,600 / 1200 = 88 samples per bit). The generateSample() function:

- Checks if we need a new bit (every 88 samples)

- Fetches the next byte from the FIFO if needed

- Processes the current bit (apply NRZI, handle bit stuffing)

- Advances the phase accumulator

- Returns the sine sample

This runs in a tight loop, filling DMA buffers fed to the I2S DAC:

while (_transmitting) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < BUF_SIZE && _transmitting; i++) {

uint8_t sample = generateSample();

sample_buf[i] = (uint16_t)((int32_t)sample << 8); // Scale to 16-bit

}

i2s_write(I2S_NUM_0, sample_buf, BUF_SIZE * sizeof(uint16_t),

&bytes_written, portMAX_DELAY);

}

The DAC converts these digital samples to analog voltages that drive the DRA818V’s modulation input. The result: clean AFSK audio that any APRS receiver can decode.

AX.25 Frame Construction#

APRS runs on top of AX.25, the link-layer protocol designed for amateur packet radio in the 1980s. The frame structure is rigidly defined:

[FLAG] [Dest] [Source] [Digis...] [Ctrl] [PID] [Info] [FCS] [FLAG]

0x7E 7B 7B 7B×N 1B 1B N×B 2B 0x7E

Each field has a specific encoding. Getting any of this wrong results in packets that transmit but fail to decode.

Address Field Encoding#

Callsigns in AX.25 are always 7 bytes: 6 characters + 1 SSID byte. Each character is left-shifted by one bit:

void Protocol::sendCall(const AX25Call& call, bool last) {

for (int i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

char c = (i < strlen(call.call)) ? toupper(call.call[i]) : ' ';

putByte(c << 1); // Shift ASCII left by 1 bit

}

uint8_t ssid = 0x60 | (call.ssid << 1) | (last ? 0x01 : 0);

putByte(ssid);

}

Why the bit shift? AX.25 predates modern protocols. The shift puts 7-bit ASCII characters into the upper 7 bits of each byte, leaving bit 0 free for control flags. For example, 'V' (ASCII 0x56) becomes 0xAC.

The SSID byte encodes:

- Bits 7-6: Reserved (

11=0x60) - Bits 5-1: SSID value (0-15), left-shifted

- Bit 0: Address extension bit

The address extension bit is 0 for all addresses except the last one, where it’s 1. This tells the decoder “no more addresses follow.” For a packet with no digipeaters:

Destination: VA7RCV-0 → extension bit = 0

Source: VA7RCV-9 → extension bit = 1 (last address)

With digipeaters (e.g., WIDE1-1, WIDE2-2):

Destination: APZMDR → extension bit = 0

Source: VA7RCV-9 → extension bit = 0

Digi 1: WIDE1-1 → extension bit = 0

Digi 2: WIDE2-2 → extension bit = 1 (last address)

Control and PID Bytes#

After the addresses come two fixed bytes:

putByte(0x03); // Control: UI frame (Unnumbered Information)

putByte(0xF0); // PID: No layer 3 protocol

- Control (

0x03): Specifies a UI (Unnumbered Information) frame—connectionless, unacknowledged data. APRS doesn’t use connected mode. - PID (

0xF0): “No layer 3 protocol.” The information field is plain text, not an upper-layer protocol.

These are constants in APRS. You’ll see them in every packet.

The Information Field: APRS Data#

This is where APRS diverges from raw AX.25. The information field contains human-readable ASCII text formatted according to the APRS spec. A position report looks like:

!4903.50N/07201.75W>Test comment

Let’s decode this:

!— Data Type Identifier (position without timestamp)4903.50N— Latitude: 49° 03.50’ North/— Symbol table separator07201.75W— Longitude: 072° 01.75’ West>— Symbol code (car)Test comment— Free-form comment

APRS uses compressed or uncompressed position formats. The example above is uncompressed. Compressed format packs position into fewer bytes using base-91 encoding but is less human-readable.

Telemetry uses a different format:

T#607,199,000,255,073,123,00000000

T#— Telemetry identifier607— Sequence number199,000,255,073,123— Five analog channels (raw ADC counts)00000000— Eight digital bits

To make telemetry meaningful, you also send PARM (parameter names) and UNIT (units) messages:

:VA7RCV-9 :PARM.Battery,Temp,Pressure,Humidity,Altitude

:VA7RCV-9 :UNIT.volts,C,hPa,%,m

These are messages, not position reports. The format is specific:

:CALLSIGN :MESSAGE_TEXT

│ │└─ Message content

│ └─ 9 characters: callsign + spaces

└─ Message identifier

The addressee field is exactly 9 characters, space-padded. VA7RCV-9 becomes VA7RCV-9 (with a space). Get this wrong and your telemetry labels won’t associate with the data.

Frame Check Sequence (FCS)#

The FCS is a 16-bit CRC-CCITT checksum calculated over the entire frame (addresses, control, PID, information). It’s transmitted inverted and LSB first:

uint8_t crcl = (_crc & 0xFF) ^ 0xFF; // Invert low byte

uint8_t crch = (_crc >> 8) ^ 0xFF; // Invert high byte

fifoPush(crcl); // Send low byte first

fifoPush(crch);

The CRC uses a standard lookup table for speed:

uint16_t Protocol::updateCRC(uint8_t byte, uint16_t crc) {

return (crc >> 8) ^ CRC_CCITT_TABLE[(crc ^ byte) & 0xff];

}

Every byte that goes into the frame (except flags and escapes) updates the CRC. If the receiver’s calculated CRC doesn’t match the transmitted FCS, the packet is rejected.

HDLC Byte Stuffing#

The frame delimiter is 0x7E. If this byte appears in the data, it would prematurely signal “end of frame.” Same for 0x7F (reset) and 0x1B (escape). These bytes are escaped by prefixing them with 0x1B:

void Protocol::putByte(uint8_t byte) {

if (byte == HDLC_FLAG || byte == HDLC_RESET || byte == AX25_ESC) {

fifoPush(AX25_ESC); // Send escape byte first

}

_crc = updateCRC(byte, _crc); // Update CRC with original byte

fifoPush(byte); // Send the actual byte

}

The receiver sees 0x1B 0x7E and knows “this is data, not a flag.” It strips the escape and continues.

Putting It All Together#

Here’s the complete frame assembly:

fifoFlush(); // Clear transmit buffer

_crc = 0xFFFF; // Initialize CRC

// Preamble: flags for receiver sync

fifoPush(HDLC_FLAG);

// Addresses

sendCall(dst, false); // Destination (e.g., APZMDR)

sendCall(src, path_len == 0); // Source

for (size_t i = 0; i < path_len; i++) {

sendCall(path[i], i == path_len - 1); // Digipeaters

}

// Control and PID

putByte(0x03);

putByte(0xF0);

// Information field

for (size_t i = 0; i < payload_len; i++) {

putByte(payload[i]);

}

// FCS

uint8_t crcl = (_crc & 0xFF) ^ 0xFF;

uint8_t crch = (_crc >> 8) ^ 0xFF;

fifoPush(crcl);

fifoPush(crch);

// End flag

fifoPush(HDLC_FLAG);

This FIFO buffer feeds the AFSK modulator described earlier. Each byte is serialized bit-by-bit, encoded with NRZI, bit-stuffed, and converted to audio samples. The DRA818V transmits the audio, and any APRS receiver within range decodes the packet.

Why This Matters#

Understanding these layers—DDS for audio synthesis, NRZI encoding, AX.25 framing, APRS formatting—explains why APRS works and why subtle bugs (wrong TOCALL, improper message padding, bad CRC) cause silent failures. The protocol stack is 40 years old but remarkably robust. Get the details right and your $20 tracker talks to a global network.

Current Status#

The tracker is working reliably, transmitting position and telemetry every 5 minutes. APRS.fi shows clean decodes, and Direwolf recognizes it as “HaMDR trackers” (the APZMDR TOCALL). Next steps:

- Add GPS smart beaconing (transmit more often when moving)

- Implement power management for battery operation

- Design an enclosure suitable for balloon flights

The hardware proved itself four years ago. Now the firmware finally matches that quality.

Resources#

- Project Repository

- PCB and Schematics

- LibAPRS-esp32-i2s - Original inspiration

- APRS Protocol Spec

- Direwolf - Essential for testing

If you’re building APRS trackers, feel free to reach out. This project taught me more about RF design and protocol implementation than any tutorial could.

73, VA7RCV